The CAN/CSA S37 Technical Committee set up the requirement for site specific calculation of the wind speed profile according to the National Building Code of Canada (Section 4.1.7). The NBCC procedures are based on Environment Canada research as published by Taylor and Lee (Simple Guidelines) paper which are also the basis for similar recommendations by other American Codes such as the ASCE 7 and TIA 222.

Unlike the other American codes, S37 does not explicitly specify the profile equations which the user can apply to his situation, leaving this task to be performed by Environment Canada or other Qualified Meteorologists. Environment Canada was tasked with providing the national wind map which is used for the Basic Wind determination and a service to provide the site-specific wind profile for any requested location on a cost-recovery basis.

The Basic Wind which is required by S37 is the hourly average wind at 10 m above ground. The map developed by EC uses the sustained wind (representing a 10 minute average in the last 10 minutes of the hour) as observed at several hundred stations across Canada. The S37 Annex E table E1 of winds for all communities with more than 10,000 population includes wind pressure values at 10 m height extracted from the EC map and adjusted for hourly average.

EC undertook to develop procedures that would provide estimates of the wind profile for engineering purposes at any height above ground, starting from the Taylor and Lee, and Walmsley and Taylor approach. which starts with the logarithmic profile at the base of a topographic feature and applying incremental changes due to terrain change and speed-up. EC then developed a single equation to encompass all effects. The reason for the logarithmic profile in the Simple Guidelines is that it represents the profile correctly up to 150 m above ground based solely on the roughness length, without the need for selecting appropriate exponents for a small class of terrain classes.

However, EC replaced the logarithmic wind profile with the power law profile in one part of the equation to satisfy the Canada Building Code procedure. The part of the equation dealing with the effect of a change in roughness on the slope retained the logarithmic correction term. This resulted in the equation generating physically impossible wind profiles when the slope roughness is much smoother than the roughness at approach to the hill.

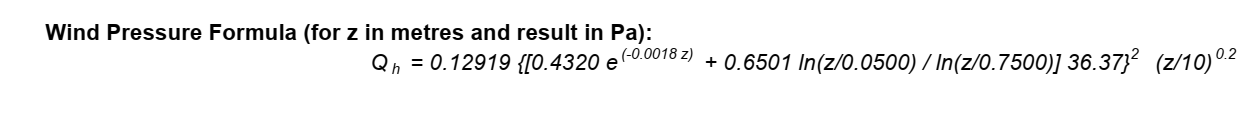

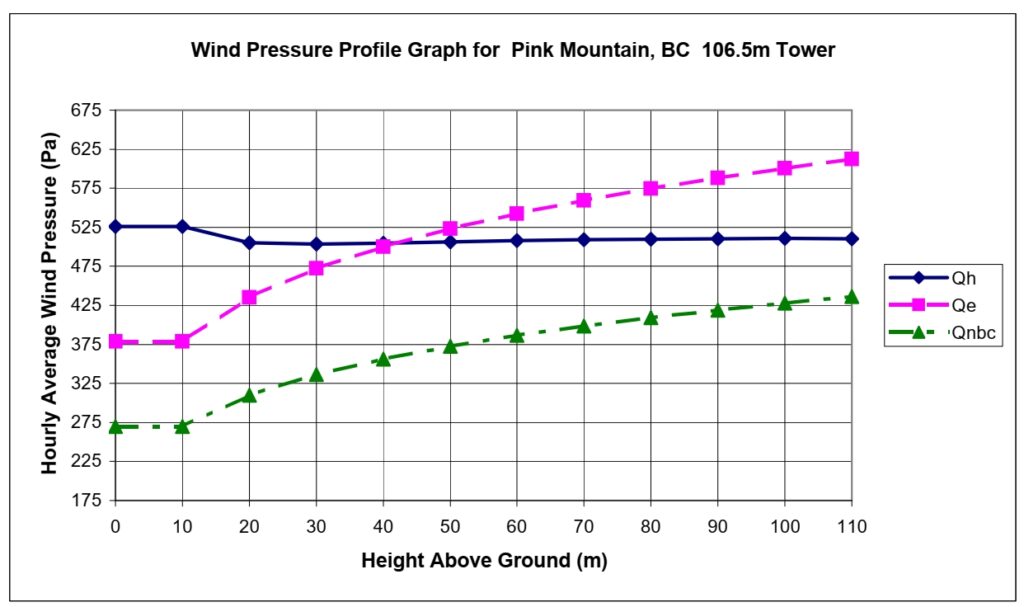

For example, the following equation and graph are from an EC report for Pink Mountain in BC using the version 1 equation.

The resulting wind profile shown in the figure below shows that the wind speed decreases with height right from the lowest level (the Qh curve). This happens because the logarithmic factor in the above equation decreases rapidly with height above ground, whereas the power law with the 0.1 exponent does not keep up with the decrease. In other words, retaining the log term within the brackets but decoupling it from the logarithmic profile produces a non-realistic wind profile.

This is why EC created the Qe profile (shown in the figure), which follows the power law profile but is calibrated to produce the same total wind pressure over the height of the tower. This led to a severe under-prediction of the lowest levels on the tower and it also failed to produce a correct total pressure on the tower since it was calibrated against a false profile in the first place. As a result of a request from the S37 committee the Qe curves were dropped from the reports.

As a result of extensive discussion between the industry and practitioners such as Ice Inc. and Environment Canada researchers, EC decided to modify the equation for the profile. But instead of reinstating the logarithmic profile they decided to adopt the ASCE7 approach of several classes of terrain (B, C and D) and calibrated the exponents to match the ASCE7 decision on classification.

The equation was also modified to deal with the situation where the roughness length changes along the fetch up the slope, as seen in the Version 2.2 equation shown below. In this case, because the roughness length changes on the slope, the formula provides two equations, one which applies up to a height 56.5 m on this tower and one for the height above up to the top of the tower at 106.5 m.

Equations for version 2.2

|

Wind Pressure Formula (for z in metres and result in Pa): |

|

|

For Z ≤ 56.5 metres: |

Q h = 0.12919 {[0.0232 e (-0.0020 z) + 1.3072 ln(z/0.3000) / ln(z/0.0600)] 46.01} 2 (z/10) 0.205 |

|

For Z > 56.5 metres: |

Q h = 0.12919 {[1 + 0.0232 e (-0.0020 z) ] 46.01} 2 (z/10) 0.205 |

|

Profile Formula General Form: |

|

|

Q h = 0.12919 {[a 1 e (-a2 z) + a 3 ln(z/z h ) / ln(z/z 01 )] v 01 } 2 (z/10) 0.205 |

|

|

Site Values of Coefficients: |

|

|

For Z ≤ 56.5 metres: |

a 1 = 0.0232, a 2 = 0.0020, a 3 = 1.3072, z h = 0.3000, z 01 = 0.0600, v 01 = 46.01 mph |

|

For Z > 56.5 metres: |

a 1 = 0.0232, a 2 = 0.0020, a 3 = 1.0000, z h = 0.0600, z 01 = 0.0600, v 01 = 46.01 mph |

Notice also that the exponent for the power law is the same in the two equations, even though the fetch roughness leading to the lower level profile is much higher than the fetch roughness representing the top layer of the tower, and one would expect a much larger exponent for the lower layer.

The reason the EC report set the exponents to be equal is that the wind speed predictions by the two equations would not match at the height of 56.5 metees. The atmosphere cannot maintain such a wind shear over a zero height interval.

The fix for this problem is shown in the more recent equations from EC reports. There is now only one equation, since the roughness length is not allowed to change on the slope.

Recent version 2.2 Equations

|

Wind Pressure Formula (for z in metres and result in Pa): |

|

Q h = 0.12919 {[0.0686 e (-0.0036 z) + 1.0000 ln(z/0.0750) / ln(z/0.0750)] 54.57} 2 (z/10) 0.210 |

|

Profile Formula General Form: |

|

Q h = 0.12919 {[a 1 e (-a2 z) + a 3 ln(z/z h ) / ln(z/z 01 )] v 01 } 2 (z/10) 0.210 |

|

Site Values of Coefficients: |

|

a 1 = 0.0686, a 2 = 0.0036, a 3 = 1.0000, z h = 0.0750, z 01 = 0.0750, v 01 = 54.57 mph |

This completes the transformation of the original equation which used continuous roughness length and allowed for a change in roughness on the slope, to an ASCE7 type of classification.

In performing this transformation, two additional errors have been made in the use of the original equation.

The first of these is that while ASCE7 recognizes that a minimum fetch is required to permit the use of say a B category instead of a C category, EC reports do not address the issue of length of fetch at all. So if there is a change in roughness from wooded to cleared at the summit, what distance of cleared fetch would be required to permit categorizing as a low roughness instead of a high roughness situation at the tower?

The second issue has to do with the choice of exponents which were made by EC. The ASCE7 presents two sets of exponents, one for the hourly average wind and another for the gust wind. When using the equations in ASCE7 one chooses the appropriate exponent according to whether the basic wind being input represents an hourly average wind or a 3 second gust.

The EC change over to the ASCE7 exponents chose the gust exponents, although the basic wind in S37 is meant to represent the hourly average wind and the wind speed tables provide the hourly average wind. Their reasoning in doing this is that the Gust Factor of 2 specified by S37-18 to deal with along wind turbulence is equivalent to 1.42 squared which happens to correspond to the ratio of gust to hourly average in the Durst Curve.

The factor of 2 is applied to the pressure profile for all heights above ground; however, the turbulence contribution to wind speed in the atmosphere actually decreases with height by as much as 20% or higher for tall towers which is why the gust exponents in ASCE7 are different from the hourly average exponents. The gust factor also depends on the roughness length (which is what causes the turbulence), and instead of contributing 42% at 10 meters the contribution can be as high 60 to 70%.

The correct approach to meet both of the requirements is for S37-18 to introduce a gust escalation factor which depends on the roughness at the site and decreases with height to correctly predict the gust wind at the higher levels on the tower. Such profiles can be generated by calculating the turbulence intensity term with height using empirical data or the Wieringa turbulence equation.

Summary

The EC single equation as modified in Version 2.2 and its current method of application do not meet the S37-18 requirement for a site specific assessment using local data and the NBCC recommended Simple Guidelines prescription for determining the speed profile.

Furthermore, the single equation approach as exemplified in Version 2.2 reports obscures the decisions made by the analyst about the terrain and topographic situation of the site and tower for the specific report being issued. The Engineer receiving the report and the Regulator reviewing the design are not provided the detail necessary to discuss and agree on the situation of the tower.

Essentially they are both asked to accept on faith that the profile being calculated by the equation according to the a1, a2 and a3 parameters as supplied in the report matches the actual situation. This is a dangerous proposition, as we have reviewed many reports such as the first one above which can lead to erroneous profiles or where the situation is completely misrepresented, such as ignoring the presence of a 200 m high ridge on which the tower is situated.

The practising design engineer and the regulator need a more complete report which allows them to spot problems, and request explanation for the choices.